Melvin Van Peebles and Blaxploitatioin

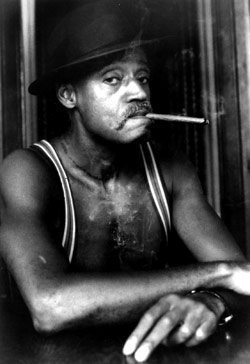

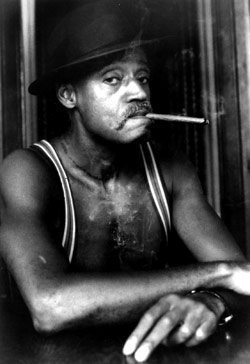

Melvin Van Peebles’

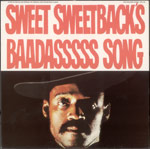

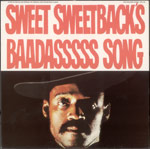

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

is universally acknowledged as the film that sparked the Blaxploitation

era in Hollywood. But Van Peebles—and his film—have a more complicated

relationship with the films and the movement that followed in its wake.

When

Sweetback came out in 1971 “black films” were few and far between. In 1969, Warner Bros. had released Gordon Parks’

The Learning Tree and Ossie Davis directed

Cotton Comes to Harlem that same year; Columbia Pictures brought out Van Peebles’s American debut,

The Watermelon Man, the following year (his first feature was the 1967 French film

La Permission

[a k a Story of a Three-Day Pass]). These films, however, sprang from

the prevailing Hollywood ethos of the day, their black stars and

directors notwithstanding (though

Watermelon Man showed traces of Van Peebles’s subversive nature, hinting at the cinematic explosion to come).

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

changed all that. Unable to find a studio to finance his 30-page ck

script, Van Peebles decided to go it alone. With a budget of $500,000

and a cast and crew made up largely of black and Hispanic

nonprofessionals, Van Peebles shot

Sweetback guerrilla-style

around L.A. over a 23-day period in May and June of 1970. Yet despite

the film’s low budget and the modest success of

The Watermelon Man,

Van Peebles could get no one to release his film. Finally, he found a

struggling distribution company on the verge of bankruptcy, which agreed

to Van Peebles’s demand for a 50% share once the movie grossed $5

million. The company, Cinemation, could only persuade two theaters to

show the film: the Grand Circus in Detroit, where the film premiered on

March 31, 1971, and the Coronet Theatre in Atlanta, where the film

opened two days later. That would soon change.

Smashing box-office records in both theaters, word spread like

wildfire through the black community, despite the fact that most

mainstream newspapers and magazines wouldn’t even review it. Soon, more

and more theaters across the country began booking the film. Van Peebles

helped to grease the promotional rails by devising two ingenious

marketing devices. The first was the simultaneous release of a

soundtrack album (written by Van Peebles and performed by Earth, Wind

and Fire—the first recording by the future R&B legends) that started

getting airplay on black radio stations, thereby ensuring that “Sweet

Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” got mentioned every time a DJ dropped the

title track. The second big plug came as a result of the RIAA’s threat

to give the film an X rating—a reaction to the raw (and frequent) sex

depicted on the screen. So Van Peebles refused to submit the film for an

official rating, resulting in an automatic X. Flipping the script on

the ratings board, Van Peebles came up with the slogan “Rated X by an

all-white jury”—a phrase that found its way onto posters, ads, and

T-shirts and became a rallying cry for black audiences from coast to

coast. “Melvin was a great marketer,” director Spike Lee says in

How to Eat Your Watermelon in White Company (and Enjoy It). “They did him a favor by giving him an X rating. Whatever they did to him he turned into a positive.”

Elvis Mitchell goes even further. In the same documentary, the former critic for

The New York Times

says, “Melvin created a controversy. His career has been built around

that, about knowing how to make noise and making controversy work to his

advantage. He made himself Bobby Seale, Huey Newton and Eldridge

Cleaver all rolled into one.”

Clever marketing gimmicks

notwithstanding, the film’s success was ultimately due to its radical

nature. Quite simply, audiences—that is to say,

black

audiences—had never seen anything like it. The scenario couldn’t be

simpler: Sweet Sweetback (played by Van Peebles)—who was raised in an

L.A. brothel—performs as the star attraction in an underground sex club.

When the cops drop by to round up some individuals for a lineup,

Sweetback is sent downtown as the sacrificial lamb to keep the law off

their backs. En route to the station, the cops answer a call for a

disturbance—apparently some young community activist is stirring up

trouble. On the scene, the cops apprehend the young man and promptly

start kicking the hell out of him. His handcuffs loosened, Sweetback can

no longer stand by idly and watch his brother get beaten anymore. He

attacks the two cops, strangling them with the handcuffs, and the two

flee. And this is just the first five minutes—the rest of the film

details Sweetback’s efforts to escape the encroaching dragnet. It’s a

90-minute chase movie, as Sweetback is forced to use his wits (as it

were; this often entails him fucking his way out of trouble, literally!)

to survive. Which he does. And that was the shocker. Here was a movie

in which the black hero kills four white cops (two others would meet a

similar fate later)—and gets away with it! The film ends with a call to

arms, a title card stating: “This film is dedicated to all the brothers

and sisters who had enough of the Man.”

As the filmmaker St. Clair Bourne explains in

How to Eat Your Watermelon in White Company (and Enjoy It),

what seemed on the surface to be a simple action-adventure story, had

deep, penetrating cultural and social significance. “Melvin is

challenging, engaging core issues in American life. Issues that people

don’t even want to talk about. And then he does it in a way that’s not

simplistic. Here’s a guy [Sweetback] who kills a cop with his own

handcuffs—and says he’s right to do it.”

It was a message

that resonated loud and clear with Huey Newton, cofounder of the Black

Panther Party. After seeing the film, Newton devoted an entire issue of

the Party’s newspaper to the film, in which he contributed a lengthy

analysis of the film’s revolutionary qualities. He made

Sweetback required viewing for all Black Panther Party members. In

How to Eat Your Watermelon in White Company…, Billy “X” Jennings, Newton’s former assistant who currently runs the Panthers’ historical website,

itsabouttimebpp.com,

describes the effect the film had on Party members at the time. “It was

the embodiment of what the Party was about. Finally, we’d seen somebody

capture our thoughts, our gestures, our ideology…so when we saw that

projected on the screen, all it did was help to empower us even more:

‘Yeah, this time they finally got it right!’ ”

Black

audiences and the Black Panthers weren’t the only ones taking note of

the film’s success and power, however. As the film became a runaway hit

(at its time,

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song was the highest-grossing independent film ever made), Hollywood came to a belated revelation: there’s an audience out there.

When MGM released

Shaft

in July of 1971, and the film became a huge hit—propelled in large part

by Isaac Hayes’s classic theme song—the floodgates were open.

(Interestingly, Melvin Van Peebles contends that

Shaft was originally written as a white detective story; that it was only changed following the success of

Sweetback,

a claim the film’s director, Gordon Parks, disputed in an interview

with filmmakers Joe Angio and Michael Solomon during the filming of

How to Eat Your Watermelon in White Company [and Enjoy It].) What followed was a torrent of black-themed studio films:

Superfly…

Coffy…

Blacula…

Black Caesar…and on and on and on. The Blaxploitation* era in Hollywood was in full effect.

But as filmmaker St. Clair Bourne contends in

How to Eat Your Watermelon in White Company (and Enjoy It), the studio suits had a different agenda in mind. “When Melvin made

Sweetback,

nobody could deny its power. But what happened was the classic American

process. Hollywood said, ‘Wow, a lot of people like this stuff. Let’s

take the formula for it, take out the politics, and give them a wave of

these films,’ and essentially, Blaxploitation is the bastard child of

Sweetback.”

Later in the same documentary, Van Peebles’s son, Mario, elaborates on this point. “[Hollywood] made

Shaft; they made

Superfly.

There was a chance for black actors to get work in leading-man roles.

But there was also something else going on. What they did was they

perverted the message. Bobby Rush, ex-Panther, Congressman Bobby Rush said to me, ‘One of the things your father’s film

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song did was it made being a revolutionary hip. And the Panthers made being a revolutionary hip. But

Superfly made being a drug dealer hip.’ Big difference.

“That impact of

Superfly

and a lot of these movies did a lot of damage,” Mario Van Peebles

continues, “and eventually, if you make enough shark movies or enough

Vietnam movies, people will get tired of going to them, and what they

did, in this case, was they shut the economic doors in Hollywood, and

they said, well, they didn’t say ‘Those action-y movies aren’t making

money anymore;’ they said, ‘Those movies with those black people aren’t

making money anymore,’ so they shut the economic doors.”

By the end of the decade, the wellspring of black-themed films had

reduced to a trickle, before drying up completely, and the

Blaxploitation era in Hollywood died a silent, unceremonious death.

—Joe Angio, November 2006 *For

more on the origins of the term Blaxploitation and the Blaxploitation

era, read David Walker’s essay from the book What it Is…What it Was!,

edited by Gerald Martinez, Diana Martinez and Andres Chavez.)

Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

is universally acknowledged as the film that sparked the Blaxploitation

era in Hollywood. But Van Peebles—and his film—have a more complicated

relationship with the films and the movement that followed in its wake.

When Sweetback came out in 1971 “black films” were few and far between. In 1969, Warner Bros. had released Gordon Parks’ The Learning Tree and Ossie Davis directed Cotton Comes to Harlem that same year; Columbia Pictures brought out Van Peebles’s American debut, The Watermelon Man, the following year (his first feature was the 1967 French film La Permission

[a k a Story of a Three-Day Pass]). These films, however, sprang from

the prevailing Hollywood ethos of the day, their black stars and

directors notwithstanding (though Watermelon Man showed traces of Van Peebles’s subversive nature, hinting at the cinematic explosion to come).

Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

is universally acknowledged as the film that sparked the Blaxploitation

era in Hollywood. But Van Peebles—and his film—have a more complicated

relationship with the films and the movement that followed in its wake.

When Sweetback came out in 1971 “black films” were few and far between. In 1969, Warner Bros. had released Gordon Parks’ The Learning Tree and Ossie Davis directed Cotton Comes to Harlem that same year; Columbia Pictures brought out Van Peebles’s American debut, The Watermelon Man, the following year (his first feature was the 1967 French film La Permission

[a k a Story of a Three-Day Pass]). These films, however, sprang from

the prevailing Hollywood ethos of the day, their black stars and

directors notwithstanding (though Watermelon Man showed traces of Van Peebles’s subversive nature, hinting at the cinematic explosion to come). Smashing box-office records in both theaters, word spread like

wildfire through the black community, despite the fact that most

mainstream newspapers and magazines wouldn’t even review it. Soon, more

and more theaters across the country began booking the film. Van Peebles

helped to grease the promotional rails by devising two ingenious

marketing devices. The first was the simultaneous release of a

soundtrack album (written by Van Peebles and performed by Earth, Wind

and Fire—the first recording by the future R&B legends) that started

getting airplay on black radio stations, thereby ensuring that “Sweet

Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” got mentioned every time a DJ dropped the

title track. The second big plug came as a result of the RIAA’s threat

to give the film an X rating—a reaction to the raw (and frequent) sex

depicted on the screen. So Van Peebles refused to submit the film for an

official rating, resulting in an automatic X. Flipping the script on

the ratings board, Van Peebles came up with the slogan “Rated X by an

all-white jury”—a phrase that found its way onto posters, ads, and

T-shirts and became a rallying cry for black audiences from coast to

coast. “Melvin was a great marketer,” director Spike Lee says in How to Eat Your Watermelon in White Company (and Enjoy It). “They did him a favor by giving him an X rating. Whatever they did to him he turned into a positive.”

Smashing box-office records in both theaters, word spread like

wildfire through the black community, despite the fact that most

mainstream newspapers and magazines wouldn’t even review it. Soon, more

and more theaters across the country began booking the film. Van Peebles

helped to grease the promotional rails by devising two ingenious

marketing devices. The first was the simultaneous release of a

soundtrack album (written by Van Peebles and performed by Earth, Wind

and Fire—the first recording by the future R&B legends) that started

getting airplay on black radio stations, thereby ensuring that “Sweet

Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” got mentioned every time a DJ dropped the

title track. The second big plug came as a result of the RIAA’s threat

to give the film an X rating—a reaction to the raw (and frequent) sex

depicted on the screen. So Van Peebles refused to submit the film for an

official rating, resulting in an automatic X. Flipping the script on

the ratings board, Van Peebles came up with the slogan “Rated X by an

all-white jury”—a phrase that found its way onto posters, ads, and

T-shirts and became a rallying cry for black audiences from coast to

coast. “Melvin was a great marketer,” director Spike Lee says in How to Eat Your Watermelon in White Company (and Enjoy It). “They did him a favor by giving him an X rating. Whatever they did to him he turned into a positive.”